Satya Nadella’s Email, Decoded

I was very excited when I read Satya Nadella’s recent public email message about his direction for Microsoft. I left the company in early 2010, frustrated with its direction. The email seemed to confirm what I had hoped about his appointment as CEO.

Then I saw Jean-Louis Gassée’s critique of the message and realized that I had read Satya’s words through Microsoft goggles. Having lived the internal corporate process that takes a few strong, simple ideas and makes them into thousands of words of compromised language, I had subconsciously decoded his message.

Here’s the way I interpreted Satya’s words. I’m not saying this is the email he could have or should have written. It is simply the words I heard as opposed to the ones he wrote.

—

In Apple the world has a company that is about simplicity. A company that in its DNA is about things that are beautiful and easy to use. But it also needs a company that is about productivity.

Microsoft is that company.

Our DNA is about getting things done and making products that help people to get things done. Sometimes those products are less beautiful and more complicated, but they do more. We do more. That’s who we are.

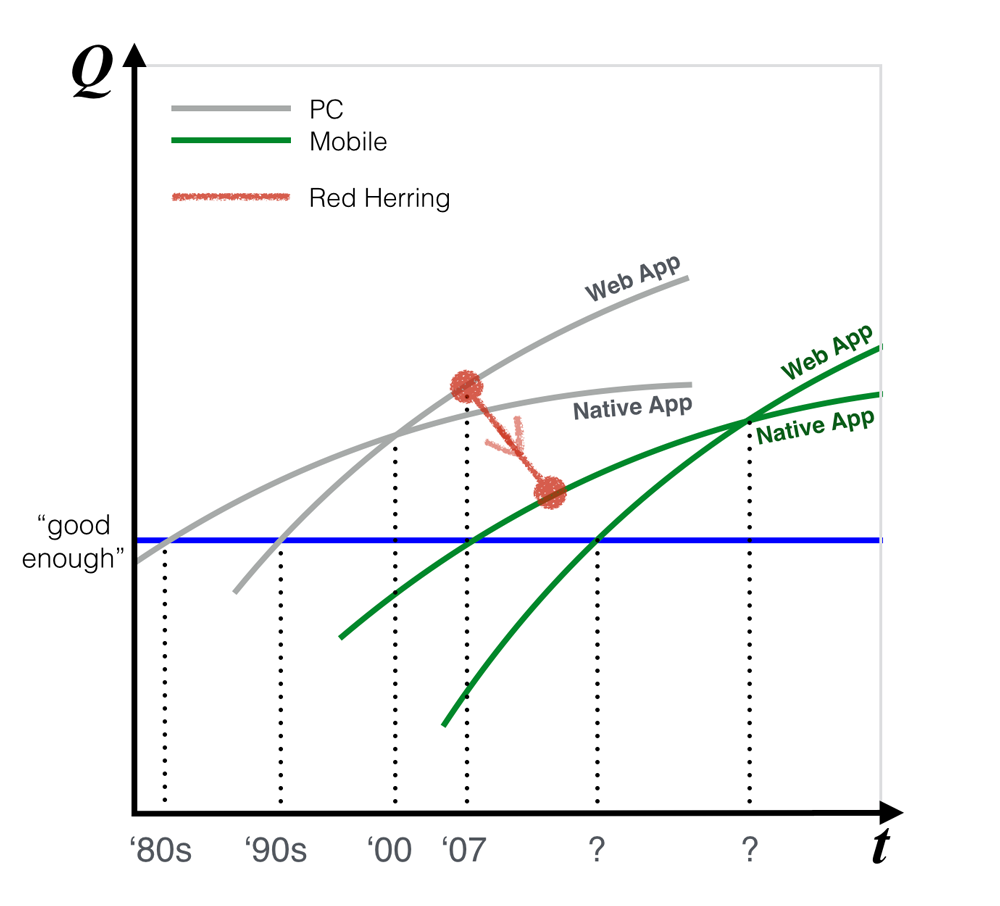

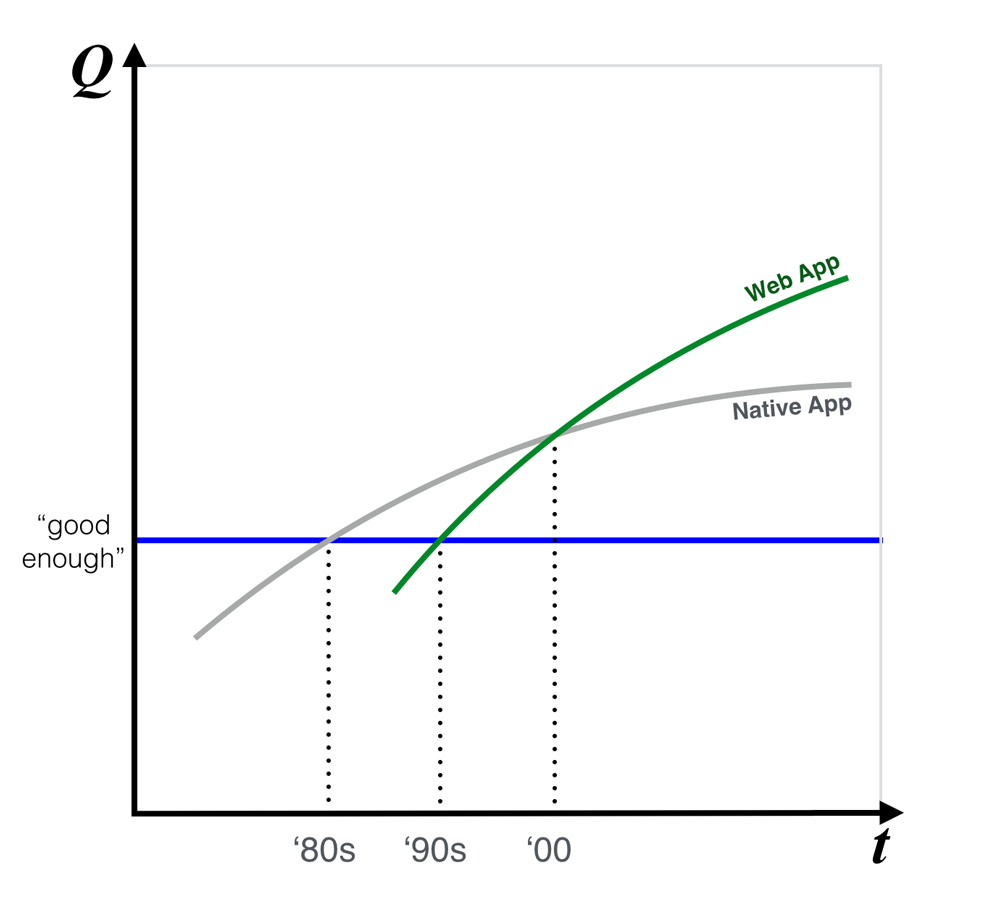

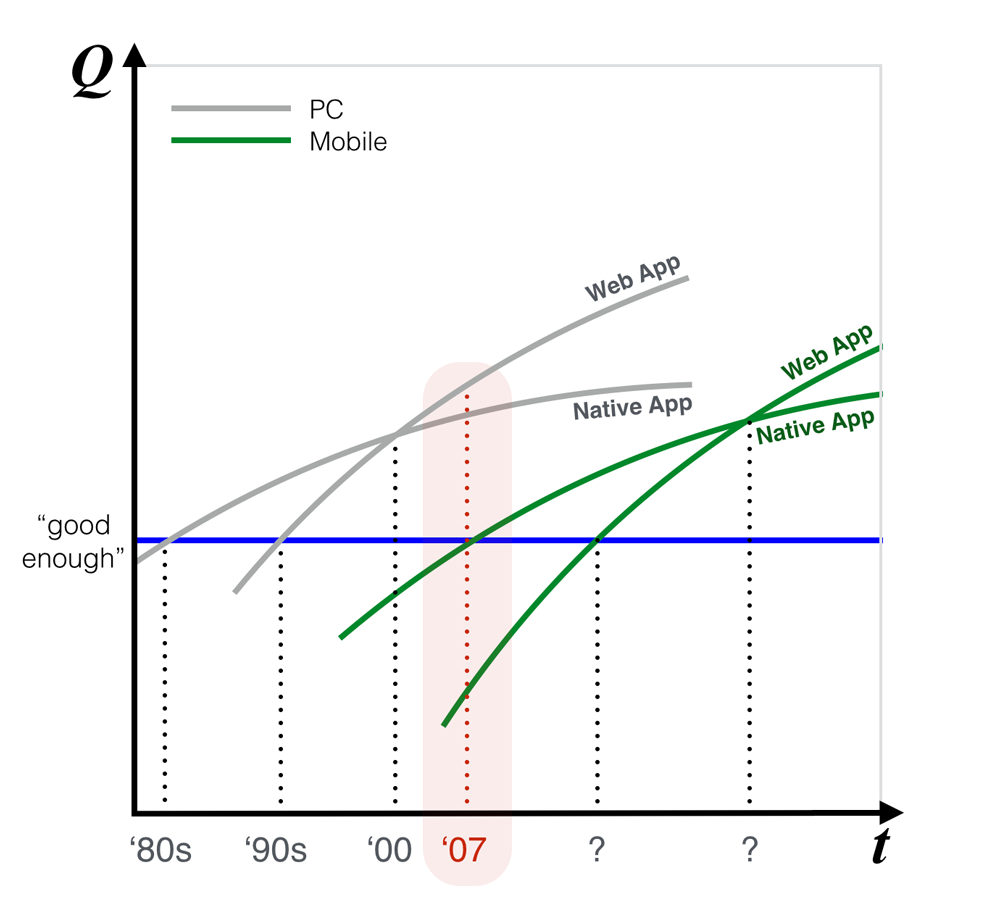

Our mistake in the past was thinking that we needed to shift our focus from businesses to consumers. And that we could make this shift with the same essential strategies as before, and by continuing to bet heavily on our client OS. This approach simultaneously took us away from our strengths and kept our thinking in the past.

Instead, we will do three things.

One, we will unapologetically focus on productivity. Of course this means business productivity, but it also means personal productivity. As people embrace mobile and cloud they will become more demanding and more sophisticated. They will be less afraid of the technology. They will want more. We will give them more.

Two, we will shift our platform priorities from the client OS to the cloud. Today the platform has exploded out of client devices and is in the cloud. That’s where the core of our platform effort will be. It will drive user experiences that are delightful on devices, but also across devices. The Windows and Windows Phone client OSs are important, but they are secondary to the platform we are creating in the cloud.

Three, our user experiences will start where most people use computing today: on their phone. All experiences are important, but mobile experiences are most important. Our thinking will be mobile-first.

We’ll need to make a lot of changes. Changes in our strategy, in our products and in our organization. Change is hard, but this change will be made easier by the fact that we’ll be returning to what we do best. And by the fact that in parts of Microsoft, like our Azure cloud platform, it has been underway for some time. Our changes will not sacrifice a current position of strength. They will take us to a position of greater strength.

Posted: July 13th, 2014 under Business As Usual.

Comments/Pingbacks/Trackbacks: none